Roll Your Own World Tour With the Internet

Disclosure: Your support helps keep the site running! We earn a referral fee for some of the services we recommend on this page. Learn more

Many musicians dream of going on a world tour. But they’re put off by the huge costs and complicated visa laws. Some assume these things put world touring out of their reach — at least without the support and deep pockets of a major label. This is not true.

Record Companies Aren’t as Important Now

Right from the foundation of Napster in 1999, the music industry has been changing. Not all of this change has been welcomed by labels, but it has been a boost to artists who work independently. Musicians who are really driven to play shows already know they can organize things themselves. The mainstream music industry is coming around to the same realization.

Prince was one of the first artists to reject major label involvement in music, having become entangled in a contract worth $100 million. In 1993, he formed his own label, NPG Records, to regain creative control. NPG Records was essentially an independent label, albeit a very well funded one. But it was perhaps the most high-profile example of a musician taking things back to basics and putting artistic control above financial reward.

Prince eventually returned to a major label, but is still credited for inspiring artists to question the way the industry works. Even prior to this, there has always been a healthy underground music scene of artists who have never sought out major label support. Fugazi is probably the best example of a band that has actively rejected it.

My Story: Printed Circuit

Just over 10 years ago, I went on a round-the-world tour with my band, Printed Circuit. It’s essentially a solo project, and it was modestly successful in the early 2000s. I’ve released records on labels like Tigerbeat6 and Darla, but Printed Circuit has never been signed to a label.

Just over 10 years ago, I went on a round-the-world tour with my band, Printed Circuit. It’s essentially a solo project, and it was modestly successful in the early 2000s. I’ve released records on labels like Tigerbeat6 and Darla, but Printed Circuit has never been signed to a label.

Printed Circuit is not the kind of band that people think of as being compatible with a world tour. Yet world tour it did. Joining me on the tour was Andrew Raine. And we completed the tour, playing shows in 8 countries over 3 months.

Not Unusual

As far as bands go, we weren’t particularly unusual in booking our own shows or tours. We just went further than most bands, geographically, for a combination of reasons. We had very little equipment, so it was easy to travel, and we’d already done a lot of touring by car. Perhaps most important, we both had a lot of friends around the globe, which made the practical aspects of a world tour much easier.

In early 2005, we saw the insides of more than 20 airports, and did our laundry in dozens of different cities around the world. It was fun to play so many shows, and it gave us a great excuse to go on holiday. Once we counted the loose change, it was (more or less) a free vacation. And for many bands, that’s reason enough to go on tour anyway.

Our 2005 world tour consisted of two separate trips. The first was to Scandinavia. The second was much larger — including the UK, Japan, New Zealand, Australia, Fiji, and the US. Andrew and I booked the tour ourselves, and paid for it from the proceeds. We publicized the band, had a lot of fun, and got back home without any major disasters.

A world tour is possible. But it’s also one of the most complicated things you’ll ever do.

Step 1: Gather Resources

Most labels hire independent booking agents, or bring in a promoter to handle most of the booking. If you are relatively organized, and you have some experience in organizing shows, you can do all of this yourself. It will take you longer than a professional agency, so that’s something to think about first.

Here are the basics resources you will need for your world tour:

Concrete

- Money. You will need enough upfront money for your visas or work permits, your travel expenses, and contingencies. Eventually, you will also need money for food as well as stuff you might not strictly need, like beer and tourist junk.

- Contacts. The more people you know, the easier booking a tour is going to be. Andrew and I were fortunate to know a lot of people, so when we combined our contacts, we could cover a very large area. This is even easier today with social networking. We mainly used email and MySpace.

- Language skills. It’s smart to learn some basics. It shows goodwill, and can be a useful tool when it’s time to get paid.

- Time. You’re going to need to send a lot of email, and you’re going to chase down a lot of people. If you need visas, allow a year to plan – at least.

- Luggage. Buy a good suitcase, and buy flight cases for all your gear. You don’t want to see your keyboard in Saran Wrap at baggage claim – particularly not after the first show. Yes, a flight case will make your gear more conspicuous. But arriving at a venue with no instruments is worse.

Intangible

- Tact. Learn about local customs if you are going to somewhere with a very different culture to your own. It’s easy to offend if you don’t know how you are supposed to behave. You could be thrown out on the street very unexpectedly, with no place to stay that night.

- Common sense. You’ll wind up sleeping in some really weird hostels. Random guys on the street will try to carry your equipment. You need to be responsible and sober enough to handle those situations.

- Creativity. Being able to think on your feet is an advantage. Anything you can do to save money is worth doing. I gave up my apartment and moved my stuff into Andrew’s house while we were away, which saved me three months’ rent. We also shipped some CDs and T-shirts to promoters, so we didn’t have to carry absolutely everything we planned to sell.

Limit Your Entourage

The more people touring, the more expensive it is. So limit who you bring.

It’s unlikely that any DIY band will take a road crew, but some take their own sound engineer on tour. My friend Michael ‘Archie’ Archibald did sound for thousands of bands at the Brudenell Social Club in Leeds, UK. Archie also traveled the world to do sound for bands like Hookworms. He passed away in September 2016. When he heard that I was writing this article, he was keen to offer some advice.

Archie recommended that you take a sound engineer if you have a sound that is difficult to replicate. Even though it’s expensive to take an extra person, it can save a lot of time and confusion each day. He pointed out that a good engineer makes the band sound good, but also acts as an intermediary to smooth over any tensions. That includes making soundchecks faster.

He also cautioned that bands never take a friend to do sound for free, unless they genuinely understand the needs of the band better than the in-house sound engineer will. Whoever does the sound must be able to do what the band wants quickly, and without causing friction, so nobody has a bad experience.

Step 2: Decide Where You Want to Go

You need a route that you can manage given your resources, as well as the equipment you are going to carry. Sticking pins in a map is a good enough start, but there are ways to make route planning simpler:

- Focus on places where you know promoters, or have friends-of-friends who put on shows. We knew people in Tokyo, Brisbane, San Francisco, and Auckland. We then approached their contacts in neighboring cities, and some promoters organized gigs on the route.

- Try to choose promoters who have a good track record. Printed Circuit played a gig in Miami with Stereo Total, which was way off course, but paid well enough to fund the detour. It also got us some press attention, which can have a valuable knock-on effect for other shows in the same area.

- Avoid places where you don’t know anybody at all. Staying in a remote place without a support network for long periods is going to be expensive and impractical. Nobody wants to spend their days off in a laundromat. (Or in a youth hostel with no windows, which is where we slept when our Adelaide show fell through.)

- Be realistic about where you want to go. Exotic places are fun, but when you’re carrying equipment, they might be inconvenient. We decided to stop off in Fiji, but didn’t play a gig there. Remember things like the fact that it isn’t easy to get laptops and suitcases on and off small tourist boats and over rocky outcrops.

Stay Open-Minded

If you can’t get a show in a particular location, ask:

- Whether any other dates would work

- If there are shows you can piggyback onto

- If the promoter has other contacts in their city, or anywhere nearby.

The more contacts you have from past shows and festivals, the easier this is going to be.

Planning Payment

Ideally, you need guaranteed fees that you arrange directly with promoters.

A guarantee is the minimum amount that a promoter will pay you, and this forms the tour budget that you can then spend on transport and other necessities.

You might be a touring band, but you could still be sent away with your cab fare if you fail to organize a guarantee in advance. At one of our final gigs in New York City, we were handed just $20 and sent on our way.

Fees are always going to be a balancing act, but merchandise sales are your friend. Printed Circuit was able to play 5 gigs in Tokyo, simply because we knew one gig would result in a guarantee. The other promoters didn’t offer guarantees, but they were worth doing to sell records. So you need to make a judgement call on how far you will travel for nothing.

Finally, you need guaranteed amounts to be made explicit: in the form of an email message or contract. And you should ideally carry a printed copy to each show.

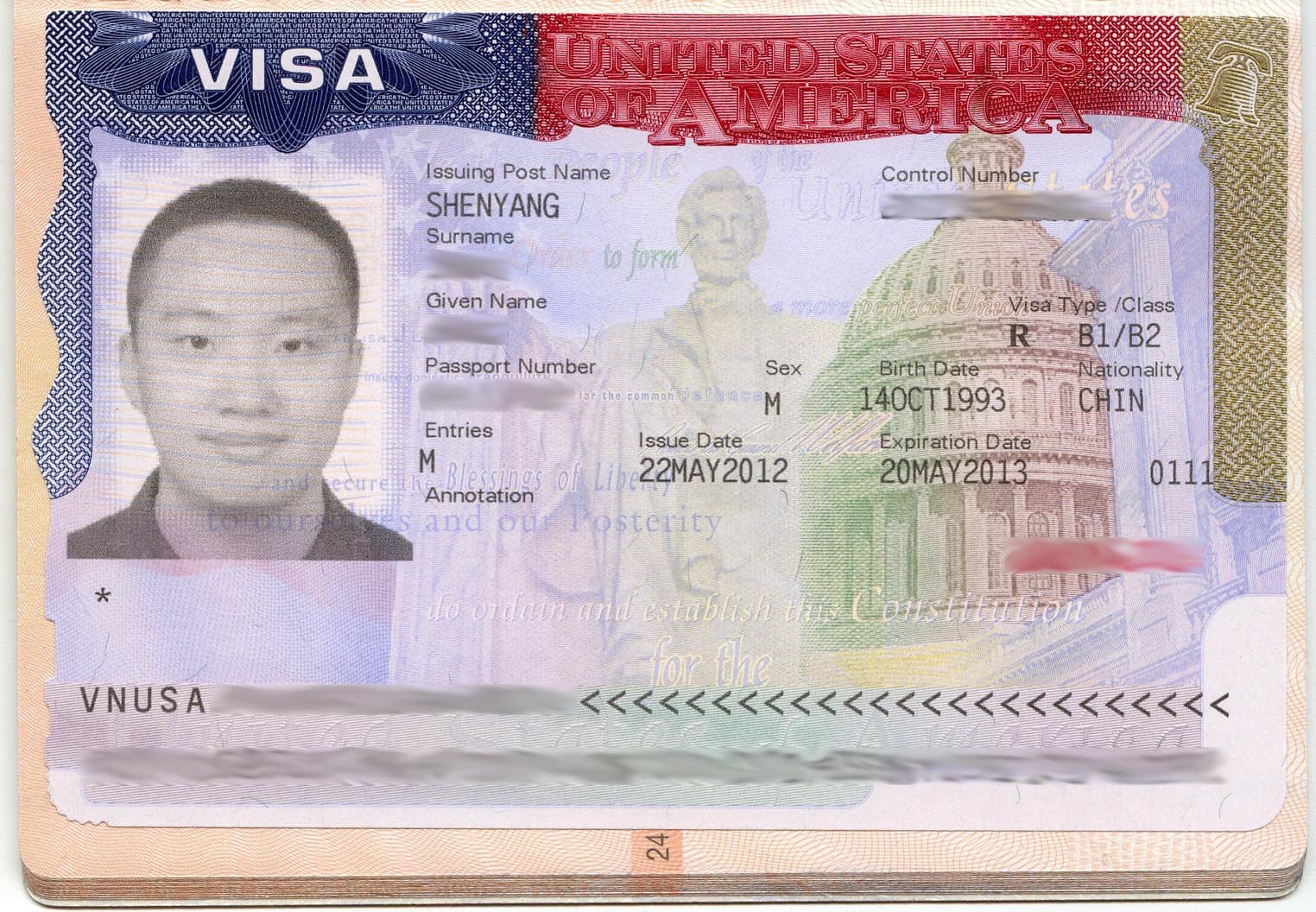

Step 3: Get Visas

Of all the steps involved in touring, getting visas is by far the most difficult.

Of all the steps involved in touring, getting visas is by far the most difficult.

In a post-9/11 world, border controls have been tightened. Anybody carrying unusual luggage will be singled out for attention. That includes odd-shaped cases, flight cases, or any box containing wires. So that includes all musical instruments, except, maybe, a GameBoy. (Yes, for a while, we toured with a GameBoy, and not much else.)

Realistically, if you want to go down the route of applying for visas, you need to be clear that you are probably gambling your money. The bottom line is this: be prepared to spend your savings, and plan well ahead.

The US visa system is probably the best example of how tough this process can be.

US Work Visas

If you’re planning to go to the US from pretty much anywhere (including Canada), you’re going to need a work visa from US Citizenship and Immigration Services. This is an expensive and lengthy process.

We didn’t apply for visas when I toured, because the immigration authorities were arguably less strict than they are now. Because I lacked any experience, I asked my friend Hilary Knott from Cowtown for some input. Cowtown is a band from my hometown of Leeds, UK, and has been invited to tour the US.

Hilary told me that the initial paperwork takes at least 6 months to be processed, but it can be repeatedly returned for additional evidence. Money-wise, Cowtown had to pay application fees, lawyers’ bills, and a fast-track processing fee.

Last Option: Fast Track

Fast-track is optional, but if you end up running out of time, you may not have the choice not to pay it. Then, even if you pay it, you still might have to wait another 6 months.

Another friend’s band, Hookworms, is signed to Sub Pop in the US. The band used lawyers to apply for visas in plenty of time for a US tour, but the application was inexplicably delayed, and the tour was cancelled.

How ever you slice it, it’s risky, and there are no refunds.

Are You Famous Enough for the US?

In terms of evidence, if your world tour is to include the US, you will need to provide proof that you’re famous in your own country.

Forget local gigs: you need concrete examples of headline appearances at large concerts or festivals. A list of all of your major radio appearances will also help.

This is the only way that US Citizenship and Immigration Services will determine your legitimacy to work and earn money in the country.

European Working Holiday Visas

Europe has myriad rules and technicalities. There’s a Schengen visa, for all countries in the Schengen zone. And there are separate visas for everywhere else, including the UK.

STA Travel has put together a list of visa requirements for different European countries. It provides a better summary than I can here.

Transporting Equipment

If you need to take equipment with you, rather than borrowing all of your equipment, you may need to buy an ATA Carnet.

Carnets are essentially passports for equipment, so you can move your gear tax-free to and from shows. You need a Carnet for 85 countries, including the UK, USA, and most countries in Europe. One Carnet works everywhere, and lasts for a year.

When you enter a country, the Carnet will be checked and validated, and the same applies when you leave. If you travel to a European Union country, the Carnet is only checked in the first and last European Union country you visit. For now, the UK is included. After Brexit, it may not be.

Being Realistic

You’re going on world tour. But you aren’t The Rolling Stones or Beyoncé. You’ll be taking care of cash, and trying to avoid getting mugged. It’s rewarding, but you need to be pragmatic. The worst thing you can do is cram too much into your world tour. Without a tour manager, you’re going to have to be disciplined, organized, and relatively sober.

For example, when we were in Japan, we found it difficult to read directions in some areas, because few signs have English translations. Simple things like this can cause delays, missed trains, and even missed gigs. So leave some breathing room.

Here are some other tips for making your tour more successful and fun:

- Give yourself spare days to relax, catch up with your email, and tour admin. Otherwise, you are guaranteed to get sick and feel awful.

- Fit in press appearances on local radio whenever it’s convenient.

- Hire a reliable vehicle and a driver you can depend on not to get drunk.

- Meet friends. There’s no better tour guide than a local person you know and trust.

- Be safe. Plan sensible rest stops, rather than constant 18-hour drives.

Step 4: Book Tickets

Now it’s time to book tickets for your world tour. Like any trip, this is an exercise of efficiency vs cost. Ideally, you want the most direct routes that you can find, while sticking to the budget determined in Step 1.

In our case, it was cheapest to book a single round-the-world ticket, which we purchased from a specialized agent. This gave us five stops from a range of choices, which we could then supplement with additional train tickets and flights. For the Scandinavian leg of the tour, we used rail passes, which are inexpensive and flexible providing you meet the age requirements.

Booking a round-the-world ticket can be economical compared to booking individual long-distance flights. It can also be restrictive, because each route is operated by a limited selection of airlines, so there will always be a shortlist of potential destinations. It’s a good idea to get some advice on the destinations you can travel to before you book any shows.

Train fares also vary enormously between countries, and timing can be crucial. In Scandinavia, rail passes are inexpensive, and for pocket change, we upgraded for extra space. In the UK, you’ll need to book rail tickets weeks in advance to avoid paying ten times more.

Funding Sources

Some bands are fortunate enough to get sponsorship for their tour. The options are very limited, but it is well worth researching in your country. For example, government money is available for Australian musicians who want to go on tour. You may also be eligible for special grants if you are disabled, or of a particular minority group.

For most bands, having merchandise to sell will be the best way to top-up your cash reserves. Often, Printed Circuit made more on merchandise than it did the show guarantee. If you plan to make use of merchandise sales, CDs are easier to carry than vinyl. T-shirt and vinyl sell well, but you may find them difficult to carry around.

Alternatively, you could try crowdfunding to raise money. Separate to the tour, I used Pledgemusic to fund one of my records. And Tom Robinson helped publicize the release on BBC Radio 6 Music. People do want to help their favorite bands, so consider this as a way to increase your funds.

Step 5: Go On Your World Tour

After all your planning, you are ready to go on your world tour.

DIY touring is daunting. Visas can consume your budget, with no guarantee of success. And there’s weeks of administration to plow through.

But if you’re realistic about duration and distance, and you have the contacts, it’s absolutely possible. Bands do it all the time, and always have done, even before the internet made it so much easier. And artists today are far less reliant on major label support. Sure, a label makes things a lot easier, but that shouldn’t stand in your way.

For Printed Circuit, booking a world tour was the culmination of many years of practicing, playing many good gigs (and some not so good), and making lots of contacts. We were initially motivated by my ambition to go to Tokyo, and we knew we had the contacts to push the plan even further. Plenty of the people we relied upon subsequently visited us on their own tours. In fact, one of the people who hosted us in Brisbane moved to Leeds, and was the bridesmaid at my wedding.

You almost certainly aren’t going to make money when you book your own world tour, and you aren’t going to be able to party every night. But you should still have a blast and come away with a break-even balance. It can open your eyes to other cultures, and increase your confidence as an individual and a musician. Again, think of a tour as a subsidized vacation and you won’t go far wrong. You definitely don’t need record label support to take a music holiday. You can do it yourself.

Header image is © 2017 WhoIsHostingthis.com. Printed Circuit at Knitting Factory Tap Bar is © 2005 Joshua Davis; used by permission. Work visa image courtesy Wikipedia; it is in the public domain. This article is dedicated to Archie with love (1975-2016).

John

May 15, 2017

I’m really into world tours but I know that the Internet can really make your planning easier and smarter if you know how to use it. The tips are quite helpful to those who are planning one since the internet nowadays is pretty much accessible, all we need to do put a little effort in it.

Dan

September 13, 2017

“He passed away in September 2016. When he heard that I was writing this article, he was keen to offer some advice.”

Advice from beyond the grave!

Frank Moraes

September 20, 2017

That is funny. But it is correct. This article took about a year to get published, and Archie was alive during the main writing of the article. Archie is something of a legend in the music community in Leeds and elsewhere.