Dodging Deception & Seeking Truth Online [Survey Results]

Disclosure: Your support helps keep the site running! We earn a referral fee for some of the services we recommend on this page. Learn more

The sheer volume of content the internet brings into our lives on a daily basis couldn’t possibly be scrolled through in its entirety. But of the content we do manage to consume, how much of it is true? And how much of it completely misleads us?

- Pages like Wikipedia contain unverified, publicly contributed information presented as fact.

- Reputable, high-ranking publications contain everything from typos to unnerving opinions.

- Even news sources must be taken with a grain of salt amidst the storm of “fake news” that never seems to end.

So how are people sifting through information? And how much of what they read do they actually believe? Is one political affiliation more discerning?

We surveyed 981 people to find out exactly that. Continue reading to see what we uncovered.

Who Do We Trust?

It’s common knowledge that much of what we consume as “news” isn’t completely trustworthy – the search for “fake news” yields over a billion results on Google alone. We know bias, mistakes, and even lies make their way into the most prestigious of outlets.

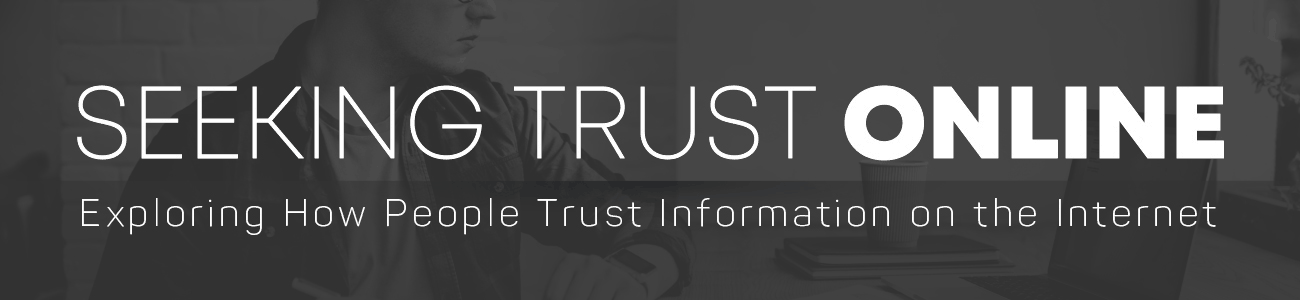

What is a surprise, however, is that news reporters are now less trusted than those openly described as “scammers.” Nearly 22% of respondents were concerned that news outlets and reporters utilized deception tactics, compared to 21.3% who felt the same way about scammers.

Sadly, political candidates and elected government officials weren’t readily trusted either, as 18.3% and 14.7% suspected these groups as guilty of deception.

If blanket trust online is impossible regardless of outlet, how do you successfully navigate through the rabbit hole and distinguish fact from fiction? Sixty-eight percent of respondents believed everything from particular sources they personally trusted. Another near 56% believed content to be true if multiple sources confirmed the same story. And less than a third were able to believe information just because the site was considered authoritative.

That means that even sites with well-established reputations were only going to be believed about 30% of the time unless they were corroborated by other sources or were personally trusted by a reader.

To Trust or Not to Trust?

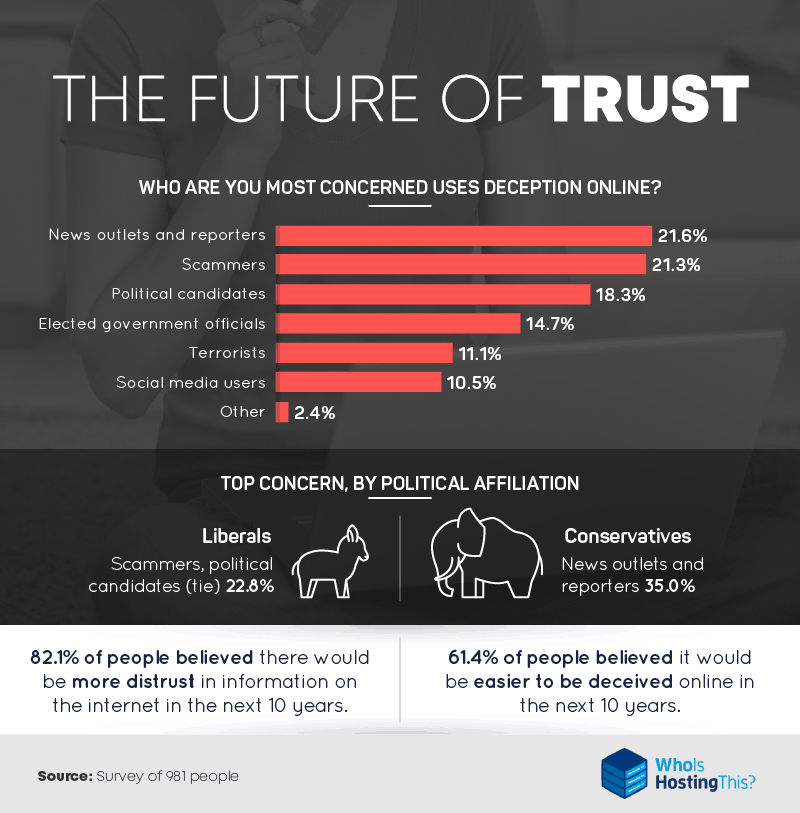

Paradoxically, everyone shared one common thought: don’t believe everyone. On average, only 56.3% of internet users were trusted to be sharing information they believed to be true, while the other 43.7% were perceived to spread false information intentionally.

Liberals were, however, more liberal with their trust, while conservatives were relatively conservative. That said, the two groups’ likelihood of believing information correlated with the source.

Conservatives were more likely than liberals to believe what they read on social media. According to one of the largest-ever fake news studies, conducted by MIT, false stories spread faster and more widely than true stories on Twitter.

The largest discrepancy, by far, existed within each group’s ability to trust news publications. While 81.8% of liberals trusted information they read directly from news publications, only 48.1% of conservatives said the same.

Current president Donald Trump has openly stated that his supporters tend to like him more when he refers to the press as the “enemy of the people,” which may encourage conservative distrust of news outlets.

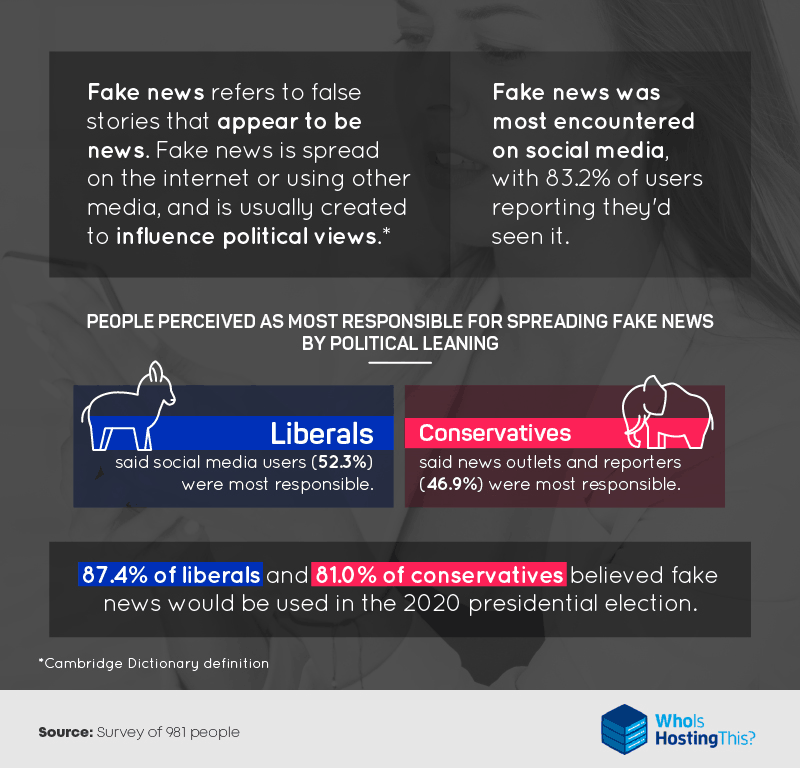

Fake news was most often encountered on social media, and liberals were more likely to call it out. Eighty-three percent of all social media users had seen what they determined to be “fake news” on a social platform at some point.

Liberals believed fake news was shared most often via social media, while conservatives believed lies existed predominantly through news outlets and reporters.

That said, both liberals and conservatives – 87.4% and 81% – believed there would be fake news involved in the upcoming 2020 presidential election.

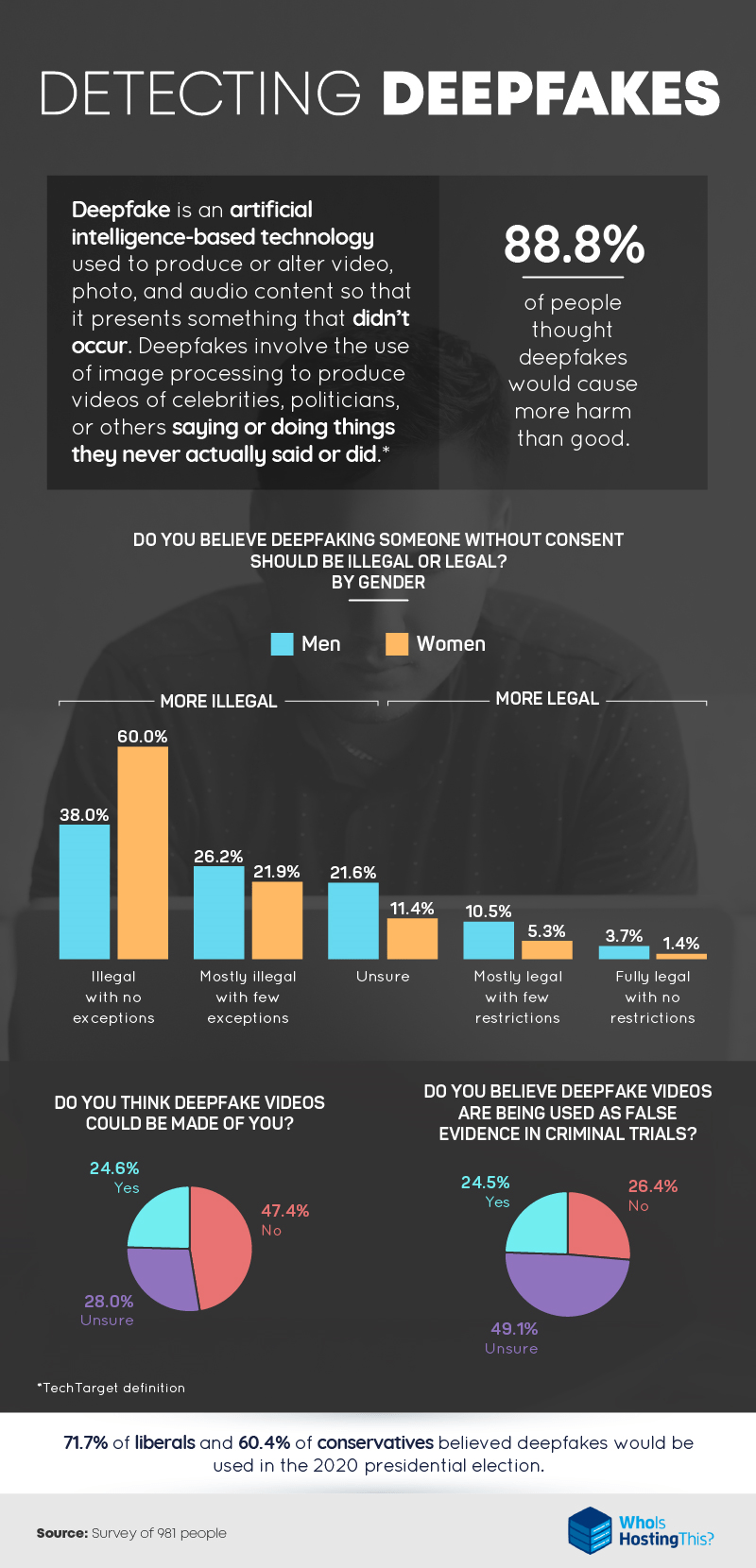

Diving Into Deepfakes

You may not have heard of deepfakes, but that doesn’t mean you haven’t encountered them. By definition, a deepfake is an AI-based technology that’s used to produce or alter video, photo, and audio content to present something that never actually occurred.

Recent examples show how difficult, or even impossible, it can be to distinguish fiction from reality using this technology. Presidential statements can be created from scratch, your voice could be recreated to withdraw money from your bank account, or your children could fake the permission you never granted them, just to name a few scenarios.

Not surprisingly, 88.8% of respondents said they thought deepfakes would cause more harm than good.

While women were much more likely than men to think that deepfakes should be illegal without any exceptions, many respondents (47.4%) felt that deepfake content would never actually be made of them.

Celebrities and public figures are more likely to be seen in deepfakes, as 44.8% of YouTube users said they had already encountered at least one example of deepfake content on the platform.

Fake Love

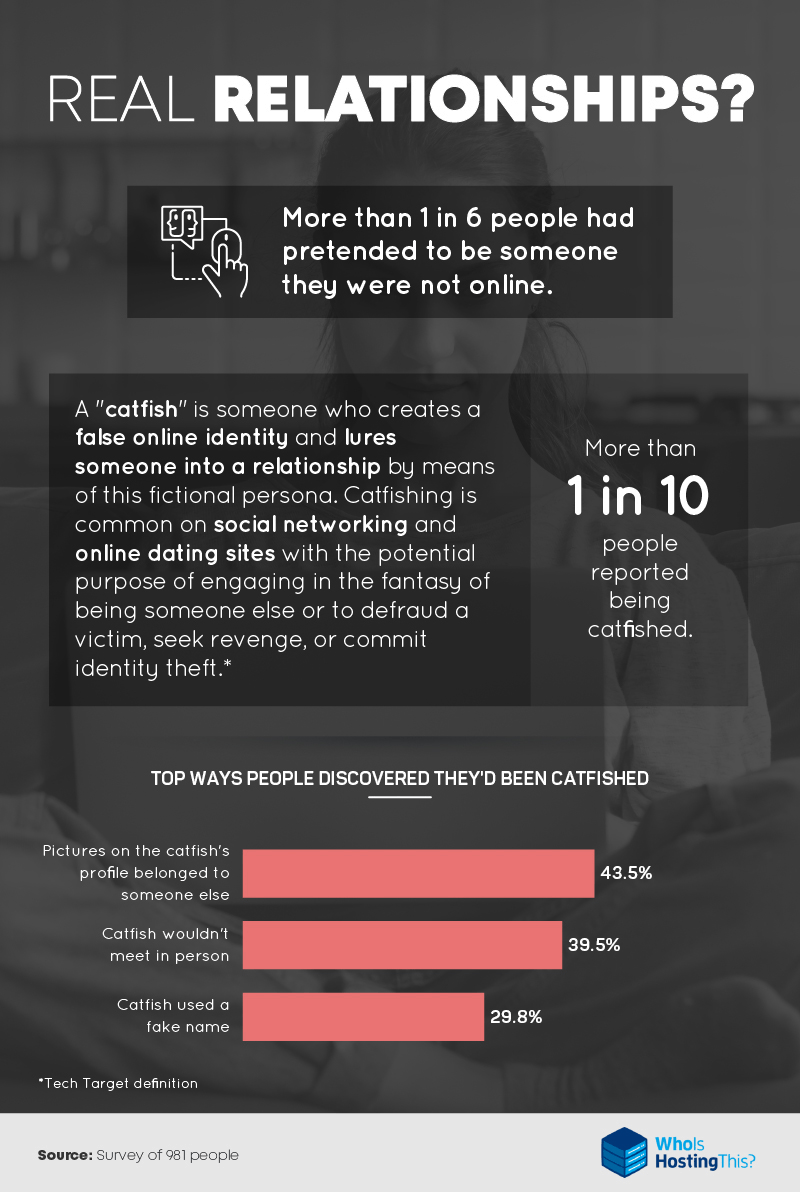

It would be remiss not to include online dating within the discussion of fake content. The term “catfish,” popularized by the film and subsequent hit MTV show of the same name, refers to somebody who creates a false online identity and uses it to lure somebody into a relationship.

Through the use of social media and/or online dating sites, deep (albeit fake) connections are forged, often leaving intense emotional scarring in their wake. Potential trauma, however, did not hinder its prominence: More than 1 in 10 people we surveyed reported being catfished before.

So how did those who reported being catfished eventually find out? Most often, they discovered that the pictures used in the catfish’s profile belonged to somebody else.

In the world of online dating, Google’s reverse image search is your friend. Another common clue that people were being catfished was that the person was completely unwilling to meet in person. This occurred for 39.5% of catfish realizations.

Though online dating continues to grow in popularity, it’s primarily important to protect both your emotions and your physical safety when considering real-life meetups with internet strangers.

Back to Reality

Whether you’re reading the news, scrolling through Instagram, or trying online dating, it’s important to protect both your perception of truth when learning and your physical safety when considering real-life meetups with internet strangers. While readily accessible and pervasive, the internet is not always safe.

What are your experiences trying to find the truth online? Are you hopeful for the future or lost in despair? Let us know in the comments below or share this information with others.

Methodology and Limitations

To collect the data shown above, we surveyed 981 internet users to learn more about their trust in online information.

To qualify for the survey, respondents were asked their political leaning, resulting in 501 people who considered themselves liberal and 480 who considered themselves conservative. Respondents who selected neither were disqualified.

Of the respondents, 315 were baby boomers, born from 1946 and 1964, 333 were Gen Xers, born from 1965 and 1980, and 333 were millennials, born from 1981 and 1997. Finally, 58.1% were female, 41.6% were male, and less than 1% identified as nonbinary.

Since data were collected through a survey and rely on self-reporting, issues such as telescoping and exaggeration can influence responses. An attention-check question was included in the survey to make sure respondents were not answering randomly.

Share Our Results

Feel like contributing some truth to the World Wide Web? You’re welcome to share this article, so long as you make sure to provide credit.

Include the following citation:

Comments